Riyadh: Thursday 16th August, 2012

As the days go by, it becomes less and less likely that the current Al Assad lead regime will survive in Syria. It is likely that it is now a question of when and how Assad falls rather than if.

Evidence for this exists in the continued failure of the Syrian Regime to suppress the popular insurgency in any part of the country, including its capital, Damascus, and commercial hub, Aleppo, the reality of the pending regime change in Syria. Yet it exists most clearly in the evidence of the increasing number of high level defectors and the attendance of all the regional players in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation Summit in Mecca (Makkah) over the last two days.

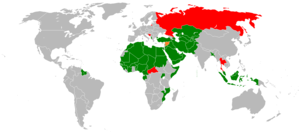

Map of nations in Organization of the Islamic Conference (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

This demonstrates clearly, that all Regional players have a deep vested interest in the settlement of the Syrian Conflict and its aftermath. Moreover, despite concerted pressure to reach a united verdict at the OIC Summit, (including intense moral pressure, applied through holding this in the Holy City at the close of Ramadan) there was little common ground, between the major players. Syria have been expelled, but there was no common message or approach.

Overnight four Sunni Gulf States, advised their citizens to leave The Lebanon immediately as a spate of kidnappings by Sunni and Shiite militias threatens to spread the ethnic conflict beyond the borders of Syria.

Whatever the pressure applied by the international community, the grass roots ethnic conflict is currently waxing, not waning, making a peaceful compromise solution unlikely. The danger is that matters may already have escalated beyond the point where the mere removal of Assad, leads to peace.

Yet it remains increasingly likely that the final makeup of the Post-Assad Syria will be affected, not by the insurgents, but by their backers.

In my last post, I outlined how the Syrian conflict, while exercising the attention and diplomacy of the global community, is non-the-less, a very intimate conflict, and like all civil wars, made all the more brutal by it being between people who will not merely pack up and go home when the fighting is done, but who will have to rebuild their lives as victor or vanquished, a process which is complicated by the complex religious and ethnic loyalties at play within Syrian society.

I went on to point out that the behaviour of some of the leading political protagonists within Syria, (notably the defection of the influential Tlass Clan to Turkey and the former Syrian Prime Minister to Qatar may seen by many as a prelude to rival bids for power in a Post Assad Syria) has exposed the complex system of patronage which has helped to sustain the minority Al Assad regime until now.

These details, often understood implicitly, within the societies in which they operate, are frequently wholly misunderstood outside the societies in question leading to real complications for powers looking to affect regime change or seeking a relatively painless transfer of power.

On the one hand, simply removing Assad, from the position of Head of State might be simple enough. But if he leaves behind the existing infrastructure of power, what has really changed? On the other hand, the advantage of retaining the existing low level bureaucracy is continuity and the retention of the infrastructure necessary for rebuilding.

As Iraq in 2003 and Iran in 1981 showed us, the collapse of a regime followed by wholesale over-throw of the existing bureaucratic infrastructure can have unforeseen and lasting consequences for would be nation builders.

In Syria, this is an especially complicated prospect. The current rebellion, fronted by the so called, Free Syrian Army, is in reality a popular revolution with substantially grass roots involvement. While we are attuned to see such movements as inherently good, this ignores the basic truth that this organisation is therefore, little more than a confederacy of competing interests, many with substantial, selective foreign backing.

Fighting under the banner of the Free Syrian Army, are a diverse array of fighters. Some (though by no means a sizeable number, are likely to be pro-western in the sense of being in favour of secular democracy. While the Islamists are likely to be split three ways, between the Turkish backed Muslim Brotherhood affiliated, the Saudi Arabian backed Salafists and a certain number of Jihadist fighters affiliated in some way, shape or form to Al Qaeda.

Then there are those who form part of Syrian minority groups, among them, Christians, Kurds, Copts. Their interests are far from heterogeneous and in reality many may support the existing regime as a way of countering the dominant Sunni Majority.

With such a diverse group of opposition interests, often with more to divide them than unify them, the way is open for a much larger and more long-term ethnic conflict to emerge from any defeat of Al Assad.

However, when looking at the vested interests currently competing in Syria, we also have to look closely at the nature of the countries backing them and in some cases, actively supporting them with weapons, advice and finance. For any one group to emerge triumphant, or at least preeminent will require for them to have amassed a level of foreign backing and recognition, and it is therefore necessary to look in detail at the vested interests of neighbouring states, regional powers and global players, to see the full picture in Syria and the region generally.

More importantly, as the current impasse between competing Islamic leaders meeting as part of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) summit organised by Saudi Arabia, shows us, the major regional players are each positioning themselves to influence the outcome of the Syrian conflict and are by no means unified along predictable lines.

The Regional Context

Historically speaking the northern Middle East has tended to be dominated by powers from its periphery. As a region the Northern Arab lands of the Levant (Modern Lebanon & Syria) and Mesopotamia (The heart of Modern Iraq) can claim, justifiably to have been the cradle of Western civilization and the first recorded evidence of a complex centralized bureaucracy takes the form of stone inscriptions recording quantities of grain stored in what is now Iraq.

This dawning owed much to its relative vulnerability as a region. The Arab lands are primarily barren and dusty, incapable of supporting the large populations required to dominate and defend the whole region. Yet, next to the mountainous regions of Anatolia, the Caucuses and Persia, the flat lands of modern day Syria, Iraq, Israel, The Lebanon and Jordan were not only fertile, but accessible, easily irrigated and traversed, but also offered easy access to the sea, through proximity to the Mediterranean, Red Sea and Persian Gulf.

As such, next to these mountainous regions, they offered untold riches. Moreover, the fact that they were relatively sparsely populated meant that to the war like tribes of these hilly regions, the prizes were all the more tempting.

It was in response to the repeated raids from these mountainous areas, that the large and oppressive (in the sense of directly controlling peoples’ lives) government bureaucracy would have developed, as people increasingly had to pool resources, cluster together in larger conurbations for protection and share harvests.

A pattern was established. The people of these regions could either submit to strong, autocratic rule characterised by strong leaders and interfering, brutal State infrastructures, or submit to foreign control.

It is the same patern which has existed ever since in the region, with Al Assad and Saddam Hussein Its most recent exponents. And the removal of one and weakening of the other is informative as to the alternative. For whenever we have week leadership or government in the northern Middle East, a peripheral power steps in to fill the vacuum.

Historic Regional Powers: Iran (Persia)

Iran (Persia): A mountainous civilization able to exert power over the flat lands of Iraq and the Levant (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

No sooner had the Iraqi ‘Strong-Man,’ Saddam, been deposed by the Americans, than a battle ensued between foreign powers to dominate the country. With America’s withdrawal, Iran had the ascendancy, playing to its links with the majority Shiite population. In recent times, Iran has similarly strengthened its links with the Palestinians and Hezbollah in the Levant and seen the Al Assad Regime increasingly fall within its sphere of influence.

Modern Iran began the Syrian Conflict on the cusp of an historic breakthrough in regional power terms. Firmly controlling the Shiite Majority in Iraq and possessing a long standing influence over Hezbollah in the Lebanon, Iran saw the potential to spread her influence from Afghanistan, (Where the Americans are managing a controlled withdrawal) to the Mediterranean. In addition, her Nuclear program offered her regional leadership and security, as well as the ability to directly threaten potential rivals and the Israeli’s, whose existence in the region at all is based upon her military and the support of the United States.

Iran’s rise is not altogether the result of American intervention in Iraq, as some people naturally assume. Iran has a young, vibrant, educated and industrious population, a tradition of work ethic and (perhaps surprisingly to those of us in the west who grew up with the Iranian Revolution, the Hostage siege and the Fatwa on Salman Rushtie), a firmly established rule of law based on the Islamic Shariah tradition. Crucially, however, Iran, is oil rich in her own right, and has used this as leverage to maintain economic relations with the International Community.

Yet Iran and her predecessors in history have always proved capable of dominating the region whenever a power vacuum develops. The specifics of her current domination of Iraq might seem fortunate or opportunistic, viewed in isolation, but, in fact, form a continuous strategic imperative dating back to antiquity.

Yet this is also true of her failure to consolidate the area of the northern Middle East. Iran’s geography, the vulnerability of the lands of Mesopotamia and the Levant, and the proximity of other regional powers make conquering these lands relatively achievable, but securing them incredibly difficult.

The former requires a powerful military, the latter, an innate ability to play off vested interests and local leaders, tribes and sects who evolve in inherently unstable regions. And this form of diplomacy requires a rare mix of loose touch Imperial control administered by loyal and knowledgeable local agents. Historically, few empires have been able to develop such an elite administrative colonial tradition, the best model of which can still be found in the English Private School System.

Finally, with considerable influence over Shiites in Bahrain, and Eastern Saudi Arabia, Iran could perceive the possibility of inciting domestic discord that would threaten to destabilise these countries and the Sunni Gulf States generally, allowing her greater leverage in the Persian Gulf.

Yet critical to this strategy is the reliance of the Al Assad regime on Iranian backing. With the fall of Assad, the likelihood would be a Sunni dominated regime backed by one of the major competing powers in the region. Iran has seen Hezbollah acting with increasing independence in recent times, and the loss of Syria would hasten this estrangement. Moreover, it would offer succour to the Sunni Minority in Iraq, directly destabilising that recovering country and weakening Iran’s hold Baghdad.

In addition, the gradual withdrawal of Russian support for Al Assad, further isolates Iran, and it cannot afford to be further isolated by standing for a dead duck.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has accepted the invitation to the summit in Mecca. Iran and Saudi Arabia have very little common ground over the future direction of Syria, or indeed, the region, but they do share a need to be involved and to have a voice in the transition, and to that end, compromise, for Iran, will slowly become the least worst option, should the Sunni rebels, backed by the Southern Arabs, gain the ascendency.

English: Map showing the territories of the Ottoman Empire in 1914, including nominal and vassal territories. http://ottomanmilitary.devhub.com/ (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Historic Regional Powers: Turkey (The Ottoman Empire)

Yet, Iran is only one of the strong peripheral nations whose mountainous terrain has allowed them to protect their own culture and intervene in or dominate the Arab heartlands. The other is Anatolia, occupying roughly the land of modern-day Turkey.

And, like Iran, Turkey has, for some time, been a country on the rise in terms of regional power projection and economic status.

It was Turkey’s predecessor, the Ottoman Empire that has been the most recent preeminent regional power, controlling almost the entire region, including the Red Sea seaboard and the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina well into the 20th Century.

While Ottoman Power in the region had been waning for perhaps two centuries from its height, its sudden collapse, following defeat in the 1914-1918 war, left a power vacuum which allowed foreign domination in the form of the British, French, Americans and to a lesser extent the Russians. The current political map of the region reflects this transfer, with the effective creation of modern Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria, the Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and the Gulf States, along their current borders, dating from that time.

Turkey, deprived of its empire, entered a prolonged period of internal self-analysis, under its newly secular leader, Kamal Attaturk, as it sought to recreate itself as a new and modern country. Turkey, following the end of WWII (In which she remained neutral), saw its traditional regional enemy, Russia, a dominant power in the Polarized Great power conflict of the Cold War. Her active membership of NATO, alliance with the United States and acceptance of American Nuclear Strike weapons on her soil all flowed from her traditional need to protect herself from any desire by Russia to assert itself at the mouth of the Black Sea. In consequence, Turkey increasingly drew away from a Middle Eastern Focus and closer to Europe.

By the dawn of the 21st Century, Turkey was nearing the end of this reflective phase with the debate around its future role revolving around whether it should focus its attention on attention on EU membership and active participation or an enhansed role in the Middle Eastern Sphere.

Today, Turkey has essentially shelved her previous enthusiasm for the former; owing in part to European reluctance to open its borders to her young, large and overwhelmingly Muslim population, but also to the growing reality that Europe’s aging populations, fiscal vulnerability and growing pacifism render her a likely backwater during the coming century, while the demographics and vast wealth in the Middle East render her unstable, threatening, but also an unparalleled trading and commercial opportunity.

A relative latecomer to the modern divisions in the Region, the Turkish government has approached the Syrian conflict in a pragmatic and cautious manner, avoiding early or active engagement while clearly offering support and shelter to the Free Syrian Army, Syrian National Council and Muslim Brotherhood.

It was to Turkey that former Assad associate and powerful Clan leader, Manaf Tlass defected and until recently, it was Turkey, which was perceived to have the greatest regional clout in a post-Assad Syrian settlement.

Turkey, however, is vulnerable in several key areas. Firstly, Syria is a hotpot of competing factions, many of whom are united against Assad, but have nothing else in common. Among these a small sect of Kurds, have sought to assert their independence in the chaos, a solution which is unacceptable to Turkey as it would lead to greater demands for autonomy among its much larger Kurdish population.

The Turks, are also likely to feel vulnerable when it comes to aggravating other regional powers. Turkey is economically stable and rapidly growing but shares common geographic interests in its North Eastern Border with the Caucuses. If Turkey announces itself as too assertive it threatens to make enemies of its long term rivals in this region, Russia and Iran. Turkey knows it can afford to play a long game in the Caucuses, and would prefer to focus on gaining regional leverage and economic wealth in the medium term. In particular, Turkey is aware of the need to focus on educating its large and youthful population for the 21st Century, something more easily achieved in a peaceful climate.

Historic Regional powers: Egypt

The other traditional power in the region is also peripheral, Egypt. Unlike the other two powers, Egypt is not mountainous on the hole and owes its historical claims to dominance to the rich cultural and military legacy which rose from its possession of the fertile Nile River and Delta, allowing it to amass extraordinary wealth and power in the Ancient world.

What Egypt has always shared with the other peripheral powers, is that it is Geographically protected.

However, Egypt’s current economic weakness is longer standing and more deeply engrained than either Turkey’s or Iran’s. Her strategic advantages, control of the Sinai Peninsula and with it control of the shortest route between Asia and Europe, was also her weakness and she has struggled to assert her independence from the Great powers throughout her history.

The Arab Nationalist, Nasser successfully negotiated the end of British and French domination with their humiliation during the Suez Crisis, but in turn was forced, through successive defeats by the Israeli’s, into the pocket of the United States, where she has remained until the Arab Spring.

Egypt’s power, at present, is limited. She is handicapped by being minerally poor next to rich Arab neighbours and her large population is frequently poorly educated and lives in cramped and dirty cities. Her recent transition from an American backed military dictatorship to a form of Islamist democracy, dominated by Mohammed Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood, will now require a period of economic consolidation to allow her government to tackle the social problems afflicting her population.

In foreign policy terms, Morsi’s moves since coming to power illustrate his lack of options. On the one hand, his sacking last week of key military advisors and removal of constitutional restrictions placed upon him by the Army seem to indicate a gradual assertion of his personal authority and his proposal to rewrite the Camp David Accords, to allow the remilitarisation of the Sinai Peninsula, appears calculated to appeal to his deeply anti Israeli constituency.

Moreover, Egypt could be expected to have significant sway over any post-Assad, Muslim Brotherhood dominated Sunni Government in Syria.

But this is misleading. The Egyptian economy has atrophied since the fall of Mubarak, and Egypt has been forced to seek a compromise with Saudi Arabia and Qatar, over funding its economy. Egypt’s population might not like it, but Morsi is forced to be as reliant on American support as his predecessor for the foreseeable future and Egypt’s reliance on Tourism requires that many of the populist policies and policy statements he might like to make are denied him by the need to encourage western tourists to return.

Then, there is the need to control increasingly confident Hamas activity near its border with the Gaza Strip and Israel. Morsi is no more keen to see lawlessness and Jihadism within his borders than the Israeli’s are or than his predecessor was. Support for the Palestinians is popular in Egypt, and a reassertion of Egypt following the humiliation of the 20th Century wars with Israel remain medium to long term goals and will require a longer game to come to fruition.

Egypt remains strategically important to the region through its control of the Suez Canal, large population, and proximity to Palestine and Israel. Egypt will continue to be courted as an ally because of her location and population, but she is some way away from exerting independent and direct influence on regional players. She is not immune to events in the wider Arab world, but is currently powerless to manipulate them independently. She will therefore seek to consolidate good relations where they exist with Turkey and (to a lesser extent), Saudi Arabia, while seeking to manage and control radical, revolutionary or Jihadist groups at home.

Saudi Arabia: A rising regional force?

Add to the mix, a relative newcomer, Saudi Arabia, occupying the vast, infertile and arid lands of the Arabian peninsula, this country would have remained a backwater of wandering tribesmen, were it not for the discovery of colossal quantities of oil. Obliged to invest heavily in infrastructure, combat internal descent and expand its hitherto nomadic population, Saudi Arabia has been slow to emerge as a regional force. Indeed, it continues to struggle to assert itself over its near cultural cousins in the Gulf States, and has yet to make a play on regional dominance. In particular, this young country has continued to be threatened by the undermining influence of Iran, whose leadership of the Shiite Muslim minority in the oil rich east of the country, forces Saudi Arabia to look inwardly at the threat of potential fifth columnists.

The Saudi, Iranian rivalry has existed since the Islamic Revolution but has generally been hidden from view by American Sponsorship of the Saudi’s and low level conflict with the Iranians.

Saudi Arabia continues to face enormous challenges to assert herself within the region. Yet immense oil wealth has given rise to an enormous baby-boom in recent decades which has required her to divert enormous resources into infrastructure, The intensely socially conservative Salafist (Wahabist) society upon which the Kingdom was founded continues to face substantial pressure from a number of powerful lobbies within and without her borders. Foreign Governments, internal moderates and external media outlets, seek reform, a process which, in turn, threatens to loosen the traditional bonds holding the society together.

Saudi Arabia is therefore required to tread carefully on even moderate reform: allowing women to compete in athletics events for the first time but requiring that they remain in tracksuits is a case in point. Crucially, the pressure to reform often ignores the ambivalence to many in Saudi Society to western values and the enormous domestic security strains reforms would have.

Pressure for reform will continue among the Shiite Minority and the restive young, especially if they feel themselves denied power by their elders or by impressions or exposure to foreign media outlets. But Saudi Arabia cannot reform without thought and care. This is also the country that gave the world a pius young man who’s support for his fellow Muslims in Afghanistan would lead ultimately to his name becoming synonymous with anti-western terror: Osama Bin Laden.

Yet despite the manifest pressures facing Saudi Arabia’s aging rulers, the country represents a significant regional player, able to turn its colossal wealth, guardianship of the Holy Cities and rapidly growing, youthful and dynamic population to influence the region generally.

This is evidenced by the OIC Summit in Mecca; Saudi Arabia’s government, seeking to utilise the end of Ramadan, approaching Eid, and its guardianship of The Holy City, to influence a binding resolution to the Syrian conflict.

In particular, while Saudi Arabia was always likely to struggle to reach a consensus with Iran at this summit, it would allow her to apply pressure to neighbouring Sunni Gulf State, Qatar, whose massive natural Gas reserves have seen her increasingly exert herself in the diplomatic stage. The Saudi’s have watched with dismay, the defection of the Syrian Prime Minister and other high profile officials to Doha, undermining Saudi Arabia’s efforts to exert her own influence in the conflict.

To Date Saudi Arabia has provided low level financial support to the Salafist elements within the Free Syrian Coalition, but a key element of the Saudi leadership has always been it’s pragmatism. Saudi Arabia, has sought compromise with Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood rulers and is likely to do the same with Iran although for very different reasons.

While the Iranians, are likely to come to see compromise over the successor to Assad, to be a necessary evil to keep a place at the negotiating table, the Saudi’s have a greater fear, that Syria could end in the sort of ethic, religious and tribal insurgency seen in Iraq in the wake of the American withdrawal. While Iran would have liked Assad to have stayed, Saudi Arabia was keen that he should go, but is less keen on a pro-Muslim Brotherhood leadership, effectively extending Muslim Brotherhood influence further, and threatening further dissention at home. Qatar’s strategy, based upon regional projection as much as concern for the Syrian settlement at home, undermines this strategy.

Meanwhile, while Iran and Saudi Arabia do not like one another’s governments, they share a mutual distaste for inviting Turkish domination of the region at their mutual expense.

Saudi Arabia has another reason as well for seeking an accord with Iran over the future of Syria. Saudi Arabia is aware that Iran remains a substantial player in the region and that, while the fall of Assad represents a set-back for their rival and a victory of sorts for Riyadh, the continued potential for Iran to successfully develop Nuclear weapons ensures that they time may come when Saudi Arabia, (and more importantly, the United States), may want to realign themselves diplomatically toward Tehran.

The Saudi’s know that they have considerable hold on American foreign policy through oil. But they also know that a nuclear Iran would change the game for the Americans, and they need to be in a position to influence its outcome.

Israel is often characterised as existing solely due to American sponsorship. Moreover, with every generation, public opinion becomes more and more hostile to the existence of the State and the subjugation of the Palestinians as a result.

The perception that Israel is merely there as a result of the Americans is partly true and at the same time not the whole story. For Israel, exists and has broadly been able to do so peacefully due to its successful military operations between 1948 and 1978. Those who argue that Israel could not exist without American sponsorship ignore the fact that the Syrians, Egyptians, Jordanians, as well as various Palestinian and Lebanese backed paramilitaries have continually put this theory to the test with no success whatsoever.

Israel’s successes in the first 30 years of her existence have dictated the regional settlement over the last thirty to the extent that Israel has been able to rely on neighbouring countries who’s international relationships with Israel have been frosty, but who have been far too weak to contemplate a further humiliation at the hands of the Israeli armed forces.

Yet while Egypt and Syria have been far too weak to contemplate attacking Israel, or even breaking the conditions of their peace treaties, they have never-the-less, continued to seek to use the existence of Israel to rouse populist sentiment in support of their government. Israel, for the old leaders, was a convenient bogy man. If there was bad news, blame the Israeli’s.

It is impossible to imagine a pro-Israeli story emerging anywhere in the Arab world, even if it were justified, and fed on such a diet, it is hardly surprising that Arab public opinion, is in no mood to compromise with Israel on any matter of existential importance.

Israel therefore has to come to terms with a new reality that its borders might once again be threatened. It does not know how the Egyptian or Syrian settlements will work out, or whether, the Saudi government will be tempted at some future point to breach its uneasy compromise relationship with Israel in some populist act of self preservation.

The Arab Spring, is not a popular ground-swelling of pent up pro-western democratic and secular instinct, although that does exist in small part. On the contrary, it is a feature of increasing dissatisfaction among the growing and increasingly vocal populations of Arab Countries that their voices should be heard.

For Israel this is threatening, because its previous policy of being a regional strong man worked well in the conventional world of regional strong-men. Mubarak could see the personal advantages of Israel being there. So could Assad, or Saddam or King Hussein of Jordan. Israel was predictable and kept the status quo in place.

But their day is at an end or rapidly approaching. A large, restive youth are waiting in the wings.

The Middle East’s Demographic Explosion

The Baby-Boom is not confined to any single Arab State. Across the Arab World, the populations are rapidly expanding in a region where oil wealth and globalisation have provided healthcare and calorie intake beyond the wildest imaginings of previous generations and suddenly provided alternatives to self-sufficiency and backwardness in an arid region.

While some countries in the region have sought to answer this massive social change through the pre-emptive use of their Oil Wealth (Qatar, Oman and the UAE have all done this), other countries, either lack the colossal wealth to do so or have not been able to access its potential until recently.

Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen, face the same social pressures exposed by a rapidly expanding population without the means to cater for this. Many people from these countries find work within the Southern Arab countries, where they are exposed to considerable wealth disparities. Many more are exposed to the aspirational lives of the young and rich, not only portrayed on American TV Channels but also in Arabic TV. A young Syrian or Egyptian can hardly be blamed for wanting to emulate the latest Lebanese Musical sensation or her pop video shot in Dubai Marina and featuring black cars reflecting Million $ yachts.

A frightening statistic, outlined by a business leader on the BBC this week, is that the Arab World, taken as a whole, needs to find 100 million new jobs within the next 25 years, just to maintain the current level of economic wealth: just to stand still.

And be under no illusions, the lesson from our own Baby-Boomer generation, is that simply standing still will not be seen as good enough. This generation will want more!

We in the west cannot ignore this. Failure to achieve growth in all Arab countries will lead to economic migration, revolution at home and possible greater radicalisation of youth. The West might feel secure from this, but our own populations are aging swiftly. It may just be that the future of Europe has many more Arabic speakers many more mosques than Europeans are typically comfortable with.

Global Powers: The Maritime Powers and the Pan-Arab Dream

The period of traditional dominance by a regional power ended temporarily in 1919, with the Treaty of Versailles and the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, and it lead directly to two distinct phenomenon.

The first was the appearance of Global Maritime Empires (Notably the French and British) as regional colonisers. Both powers had long exercised what were termed spheres of influence within the region (notably at the Maritime choke points such as Egypt, Oman and Aden). But until now, they had not actively set out to colonise problematic areas of little or no economic value. Instead, fearful of Russian Domination, they had supported the crumbling and jaundiced edifice of the Ottoman Empire, for the sake of regional security.

Now, with the Ottomans no more and the Russians humbled, the requirement (as the British and French saw it) was to ensure that the areas liberated from Ottoman Rule were smoothly administered. Both victorious powers grabbed territories on either side of what became known as the “The line in the Sand.” France got The Lebanon and Syria, Britain got Palestine and Jordan to add to it’s already de facto control of Iraq, Kuwait and Persia.”

The second phenomenon which arose from the replacement of a Regional Power with a Maritime Colonial Power, was the idea of a Pan-Arab Federation or Caliphate. Actually this is disingenuous. Such a dream has existed as long as there have been Arabs to dream it and had often been encouraged by the British (most famously, by T. E. Lawrence during the Great War) as an intellectually convincing way (on paper) of replacing the troubled Ottomans and resisting Russian Ambitions in the region.

But the dream gained currency from having been so nearly delivered before being snatched away.

Unable to realise a Pan-Arab Kingdom as they had dreamt when fighting the Turks, the Arabs’ grievances would fester and occasionally spark, while the great Maritime Colonial powers struggled to stave off a second great conflagration.

WWII, The End of the Colonial Period and the Rise of the Pan-Arabist Strong Man

With no equivalent of the Ottoman Empire to fight during the Second World War, the Middle Eastern Theatre was largely a side show. True, for the British, there was the need to extinguish Vichy French forces in Syria. True too that the British could have faced existential threat to her Empire in the Far East, Australia and India had her control of the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal been ended by Rommel’s Africa Corps. But however much the British would come to see the Desert as a crucial theatre, the reality was that in the main the protagonists fought the decisive battles in Eastern Europe, Western Europe and the Pacific.

This changed in the immediate aftermath. The Great maritime powers were now the Soviet Union and especially, America, although it would take the French and British a long while to fully grasp this new reality. It was under American pressure, that the British Set up the State of Israel, and again, under American pressure, that she and France abandoned their efforts to take back the Suez Canal when it was annexed by Egypt’s Colonel Nasser.

Thus, from the Great powers arose both the dream of Pan-Arabism and a generation of its anti-imperialist, sometimes proto-Marxist Leaders. Nasser, would be joined by Gadaffi in Libya, Assad in Syria, Saddam in Iraq, Arafat in Palestine, as the era of the pan-Arabist, socialist militarist President-cum-Dictator gripped much of the Arab world.

It is no coincidence that this generation of leaders and their successors, would succumb during the ‘Arab Spring.’

Young, often glamorous, and macho, these men were virile embodiments of a sort of anti-colonialist freedom in their hay-day, as the French recoiled violently from North Africa and the British wavered and then surrendered their claims to their possessions in and around the Gulf, it was these men who embodied the hopes of the Pan-Arabists for a brief and fleeting moment.

United States and Soviet Union and countries lying within their sphere during the cold war. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Cold War

Inevitably perhaps it was all too much. They could never exert themselves in a regional sphere increasingly dominated by the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States. Increasingly, the Strong men were drawn into spheres of influence, either allied to one or the other. Egypt and Turkey would be drawn firmly into the American Sphere, as would the Shah’s Iran, before the revolution. Saudi Arabia too, and to a lesser extent. The Gulf States, whose traditional ties with Britain would survive independence and the Oil Crisis, would align themselves with the Americans, often for protection. Yemen, would be split by the great East/West Ideological divide while Iraq, would tolerate the Russians, in opposition to the Shah’s pro- Americanism while Syria would do like-wise in opposition to the Turkish membership of NATO.

Increasingly the Strong Men, were seen for what they were. Small men in the global sphere, mere pawns in the battle between East and West in which it was in both Superpowers’ interests to keep the Middle East divided. Once glamorous and virile, these men were now podgy, petty patriarchs whose regimes, characterised by brutality, had little to recommend them.

Saddam’s posturing in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union should be seen in this context. His reputation was as the Strong Man. Yet, his Soviet era weaponry was no match for Western power and he knew it. What he was left with was swagger and bluster. Ghadaffi and Mubarak played more flexible games and lasted longer, though not much longer. Assad, will certainly not survive the current crisis, though his regime might yet still do so under a different leader. If it does, it will be as a further diminished force, heavily reliant on a foreign backer for support.

The Current Great Power Response to Syria

The American obsession with the Middle East since the fall of the Soviet Union has been welcomed privately by Beijing and Moscow, allowing as it has, these two former Communist Giants to restructure their economies, reassert their power internally and gradually work to begin amassing Power Projection capabilities.

The result is that Russia increasingly holds powerful sway in most of its former republics and leverage in many of its former satellites, While China has pursued an increasingly assertive outlook in the South China Sea and has sought actively to develop economic influence and partnerships in resource rich regions as diverse as East Africa, Greenland.

The resultant Great power outlook is, in consequence, far more complicated than it would have looked even a decade ago.

On the whole, Russia has been disappointed by the path the Syrian crisis has taken. While having no real strategic interest in the area, she has none-the-less opposed US attempts to manage a direct influence at regime change for two reasons. Firstly, Russia objects to Western piety, on regime change as it has often threatened Russian interests (as it did, when the US supported Ukrainian and Georgian revolutions in areas Russia deemed her sphere of interest). Secondly, Russia was happy that Iran should strengthen its sphere of influence in the northern Middle East as this would help apply destabilising pressure on American ally, Turkey and possibly even draw America back into active Middle Eastern engagement, taking away any focus on Russia.

Disappointingly, for Vladimir Putin, neither of these scenarios currently looks the most likely. However, this was never crucial for Russia, who’s key strategic interests in the Middle East lie in the Caucus Region and to either side of the Caspian Sea where several former Soviet Republics, notably Tajikistan, and Azerbaijan, are increasingly influenced by assertive Islamic teaching and political affiliates to the Muslim Brotherhood.

China’s interest in Syria, is likewise, marginal. Moreover, China has tended to follow Mao’s foreign policy dictum that China should not offer world leadership or enter foreign policy entanglements but remain active in areas where China’s own national security is directly at stake. Yet Beijing shares Russia’s desire to see the US’s attention drawn away from her own activities for as long as possible and has tended to oppose US attempts to influence the course of the conflict through the UN.

France, as former colonial mandate, maintains, an interest, if not exactly a strategic one. As such, France could be expected to have been extremely vocal in support of the Syrian rebels, as it was in the intervention in the Libyan Revolution and in brokering a ceasefire between Russia and Georgia.

That France has been relatively meek on the issue is an indication that the new French Socialist Party of François Hollande has been firmly focussed on French domestic issues, and is less comfortable with foreign power projection than his predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy.

In part, this is a reflection of the French Socialist Parties heritage as a party used to forming opposition to the Gaullist Tendencies of Frances right of centre party. Partly too, the confusion of the Socialists response reflects the fact that much of their mandate was received from ethnic minorities and France’s substantial Muslim population.

However, the uncharacteristic quietus of France over Syria is also evidence of the weakness of France generally. Beset by domestic discord, much of it ethnic in origin, and facing a sustained crisis in economic terms, partly through Euro membership, France is facing a crisis of confidence. Moreover, France, who until recently, maintained a substantive level of independent foreign policy from NATO was sorely chastened by her experience in Libya, where her bellicosity and rapid commitment to military intervention exposed the complete absence of her capacity to intervene independently of the US. While pride ensured that Mirage aircraft dropped bombs on Libya, they were wholly reliant on US airborne command and control facilities and reconnaissance.

William Hague: British Foreign Secretary (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Britain

Britain shares many of the same problems, though is perhaps more secure economically. However, her voice is doubly subdued by her having next to no historical interest in the Levant. Here population perceive no strategic interest in the area and thus, Britain’s response has been limited to muted condemnation of humanitarian abuses. This is reflected in her response to the crisis, announced earlier, this week, by Foreign Secretary, William Hague. GBP5 Million, is by the standards of Britain’s overseas commitments in other countries, a poultry figure recognising the limited influence Britain will likely have in the region, regardless of the composition of the next Government.

The United States

This leaves the US. America, unlike Britain, perceives a limited Strategic interest in Syria itself, not least because of her direct proximity to Israel. Moreover, the US does not want to see Syria in the pocket of Iran, as that sphere would threaten the balance of power in the region and tie America down there for a generation.

The US, as a democracy, is not always entirely free to pursue its National Interest and requires to justify its interventions in moral terms. The current administration has acted correctly in realigning American priorities toward Asia Pacific, but has continued to support regime change on humanitarian grounds and, less vocally, on the grounds that it would like to weaken Iran in geopolitical terms.

However, the current American administration has struggled to extricate itself from the Middle East Theatre, partly because its policy is dictated by the ongoing strategic imperative governing all American administrations since the second world war, that the regional balance of power should be maintained ensuring weak, divided governance and minimal threat to regional dominance from any one country.

This leaves the current administration open to dangerous critique in an election year, further limiting the American scope for manoeuvre. At present, therefore, America has tended to act through proxy, and distant statement in support of efforts to engage in peace talks. America will not intervene militarily, however regardless of the victor in Novembers elections and will therefore have limited scope for asserting its interests beyond supporting the diplomatic manoeuvres of allies for the foreseeable future.

Syria’s Future?

As I have stated above, the Syrian conflict has been escalated by the manipulation of pre-existing regional tensions by regional powers, none of whom are prepared to act directly to end the conflict, but all of whom have sought to position themselves to take advantage of the end-game to the Syrian conflict.

The tragedy of this is, of course, that it is the ordinary Syrian (and possibly Lebanese) people who will suffer directly as this conflict continues to escalate. Yet, it is also clear when looking at the international response to Syria, that the Levant Region reflects many of the ongoing regional divisions and interests in microcosm. As increasingly, Syria follows the path of so many Civil Wars in attracting foreign fighters from across the world to take part in the conflict, and as money, weaponry and associated equipment find there way through middle men from foreign capitals to the arms of the combatants, it is highly unlikely that this conflict will end in a negotiated ceasefire in the immediate or predictable future.

Indeed, it has become increasingly likely that, thanks to the influence of foreign powers, the conflict to depose Assad, may well result in a longer conflict as the many competing interest groups in Syria are robbed of the current unity of purpose his regime provides.

With the Sunni insurgents far from unified in their own purposes, it is quite possible that with the fall of Assad, will come the removal of any nobility of purpose behind the insurgency. If that happens, Syria will decend into the sort of bloody, and grubby little conflict we have seen in so many civil wars, in places like Bosnia, Latin America, The Lebanon and Africa, in the past.

Some Civil Wars are redeemed by history despite the appalling wounds they inflict on societies. When the final body’s are laid to rest, the people left behind discover that something nobler came from the conflict, something which helps to define the nation and its people to future generations.

Yet, for every American Civil War, there is a Rwanda, a Bosnia, a Spanish Civil War. These conflicts are no more or less messy, bloody or futile, but when the die is cast, we find less to redeem them, less for the survivors to build their remaining lives around.

In such conflicts the winners and losers are hard to distinguish. The victors are seldom distinguished by their victory, the vanquished seldom possess unequivocal moral righteousness or guilt. Instead, the best that the survivors of such wars have, is the ability to say that they have seen the evil in politics and people and now wish to forget what they have seen. TYhere are no winners in such a conflict. Everyone left behind in the post war landscape is diminished.

Yet there are winners to such wars. Though it is unlikely that you will see Turkish, Iranian or Saudi regulars taking any part in the civil war, they will continue to feed its combatants as long as they feel it is worth doing so. For these nations, the outcome of the Syrian conflict can affect the power they bring to the peace conference table and as such, will directly influence their ability to project national power in the region for a generation.

There is no prospect of such a conference now. The way is still escalating, drawing in the latest generation of jihadists or pious youth willing to die for a great cause. But this phase will end in time, and increasingly, diplomats and medics will find their voices being heard. Politicians will judge the mood and eventually a compromise will be reached whereby the protagonists will meet to negotiate a settlement.

Grubby men with skeletons in closets will find they have smart new offices and ministerial vehicles. Perhaps, for some, respectability awaits. But they are not the real victors either. Such men never escape from the pockets of their benefactors. It will take succeeding governments to assert Syrian independence. Even in relatively clear cut wars such as that in 1930’s Spain, the victorious Franco only really emerged from out with Hitler’s shadow, as the Nazi’s themselves faced defeat.

And yet none will deny the real victor of Spain’s Civil War. Germany emerged an intimidating and practiced military force. The rest of Europe struggled when facing the German Army in the 24 months that followed.

So it will be in Syria. A peace conference will be called and various parties will settle on a way forward, some winners and some losers. But the real winners and losers will be the mediating nations.

Put simple, in the aftermath of the Syrian Civil War, Syria will be weakened. But some of her neighbours, perhaps the Turks, perhaps the Saudi’s will be strengthened. It is that which leads them to support the combatants, and it is that which will determine their diplomacy.

In a Civil War, there is no cavalry over the hill, at least none which is not slightly tainted by being there.